Using pictures to develop an argument, unpack the following words from Elizabeth Edwards:

“Central to the nature of the photograph and its interpretive dilemmas is its insistent dislocation of space and time… Closely related to the temporal dislocation in a photographic context is spatial dislocation. In the creation of an image, photographic technology frames the world. Camera angle, range of lens, type of film and the chosen moment of exposure further dictate and shape the moment. Exposure is an apposite term, for its carries not only technical meaning, but describes that moment 'exposed' to historical scrutiny. The photograph contains and constrains within its boundaries, excluding all else, a microcosmic analogue of the framing of space which is knowledge."

The above extract is taken from an essay written by Okwui Enwezor and Octavio Zaya entitled 'Colonial Imagery, tropes of Disruption: History, culture and representation in the world of African photographers.'

The essay was specifically written to accompany a photographic installation that was on display at the Guggenheim Museum, New York in 1996. The exhibition was entitled ‘African Photographers, 1940 to present.’ Unfortunately the Guggenheim Museum only began making past exhibitions available on their online archive recently, and so the collection of images referred to cannot be viewed.

Without the visual references, a basic description of the exhibition informs us that the production included a selection of photographs from 30 African Photographers from diverse racial, cultural and spiritual and even geographical contexts.

The purpose of the exhibition sought to explore the perceptions of both Westerners and Africans in relation to Post Colonial Africa. With this background in mind, it becomes apparent why the authors chose to quote Elizabeth Edwards in their essay. Edwards is an academic lecturer at the University of Oxford who is regarded as a thought leader on photography as an anthropological tool. Her latest book published in 2004, ‘Photographs Objects Histories’ repeats many of the sentiments she raises in the essay published eight years prior.

Edwards in a nutshell:

The main theme introduced by Edwards suggests that as a result of the ‘dislocation of time and space’ as is uniquely possible through the technology of photography, the viewer is not given the historical context of the picture. But the photographer does have a certain power over his viewer by being able to 'dictate and shape the moment.'

The extract from Edwards – as is typical with academic writing is its unnecessary complexity. Her use of verbose language has a neutralising effect on her argument.

Edwards first introduces the concept that spatial dislocation is closely related to temporal dislocation and that this is the central nature of photography. However having made such a profound statement that manages to drill down to the snapshot essence of photography, she contradicts herself a paragraph later by spouting vague and broad phrases such as photographic technology being capable of ‘framing the world.’

Her argument takes yet another swerve when she returns to the snapshot concept using the technical term 'exposure' as an analogy for a 'moment in time'. Since the analogy fits well with her initial musings on the dislocation of space and time, her words regain some credibility, however she insists on steering her reader back into the fog with the introduction of more obscure theory - this time from Neoplatonists debating theories of interpretation.

The concept of a microcosmic analogue was introduced by James Coulter in his book entitled ‘the Literary Microcosm.’While Coulter quotes Plato as saying ‘A literary composition must resemble a living thing’, what Edwards appears to be attempting is the suggestion that only living photography or that which captures real life – like ‘living literature’ will succeed in framing time and space and therefore ultimately lead to knowledge.

While I find the overly complicated writing of the essay frustrating, I was able to distill some semblance of wisdom in her time and space theory.

To illustrate this, I've collected three black and white photographs of traditional rural scenes in Kenya. One of the images was taken in 1939, another in 1961 and the last in 2005. Each represents a vastly different social context from the others...

In my opinion, nowhere is the moral question of cultural integrity in relation to post colonial Africa more poignant than in the Maasai people. In present time, it is not uncommon to find 'Maasai warriors' serving curry at a buffet of a safari camp or to find Europeann tourists posing alongside Maasai people clad in tribal blankets, wedding necklaces with painted faces.

Key to reading the images:

This image of Kikuyu Children in Kenya befriending a European girl was taken in 1939. It is a famous image about a family who took refuge in Kenya after being persecuted as Jews in Europe and ultimately making Kenya their home.Other than the porcelain hand painted doll and possibly the costume of the little girl, there are few temporal clues as to the image's date.

This image of Kikuyu Children in Kenya befriending a European girl was taken in 1939. It is a famous image about a family who took refuge in Kenya after being persecuted as Jews in Europe and ultimately making Kenya their home.Other than the porcelain hand painted doll and possibly the costume of the little girl, there are few temporal clues as to the image's date. This image was taken in 1961 by James Burke of the Evangelist Billy Graham talking to Maasai herdsmen. The image for me still suggests a strong sense of paternalism of European culture and spiritual beliefs over Africa. Perhaps without the background context of Billy Graham, the European man on the left could have been a tourist...in any time frame?

This image was taken in 1961 by James Burke of the Evangelist Billy Graham talking to Maasai herdsmen. The image for me still suggests a strong sense of paternalism of European culture and spiritual beliefs over Africa. Perhaps without the background context of Billy Graham, the European man on the left could have been a tourist...in any time frame? This image was taken off a tourism website promoting 5 day cultural tours with the Maasai. It was taken in 2005 and a throng of European tourists standing to the left of the image have been cropped out. The seeming authenticity of the gathering along with their clothing suggests to me that this image could have been taken at any time in the last sixty years, but it is the power of the photographer to 'dictate and shape the moment' that has compromised the integrity of this image as authentic documentation of culture.

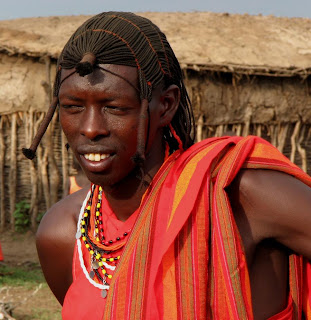

This image was taken off a tourism website promoting 5 day cultural tours with the Maasai. It was taken in 2005 and a throng of European tourists standing to the left of the image have been cropped out. The seeming authenticity of the gathering along with their clothing suggests to me that this image could have been taken at any time in the last sixty years, but it is the power of the photographer to 'dictate and shape the moment' that has compromised the integrity of this image as authentic documentation of culture. The image on the right of a young Maasai man was taken at a cultural village outside the gate of the Masai Mara Game Reserve. He is employed at safari lodge in the reserve and much of his income is dervied from tourists wishing to take photographs alongside him. If the viewer is aware that this image is taken in a cultural village staged for tourists, does it still count as a legitimate cultural experience? Does the man int he photo, who earns his living as a tourist model rather than a herdsman, still qualify as a Maasai warrior?

The image on the right of a young Maasai man was taken at a cultural village outside the gate of the Masai Mara Game Reserve. He is employed at safari lodge in the reserve and much of his income is dervied from tourists wishing to take photographs alongside him. If the viewer is aware that this image is taken in a cultural village staged for tourists, does it still count as a legitimate cultural experience? Does the man int he photo, who earns his living as a tourist model rather than a herdsman, still qualify as a Maasai warrior? Juxtaposition and cultural pollination is inevitable. But what comes next? Maasai warriors posing in top hats and tails alongside the Queen in Buckingham Palace?

Juxtaposition and cultural pollination is inevitable. But what comes next? Maasai warriors posing in top hats and tails alongside the Queen in Buckingham Palace?Your comments are welcome....let the discussion begin

No comments:

Post a Comment